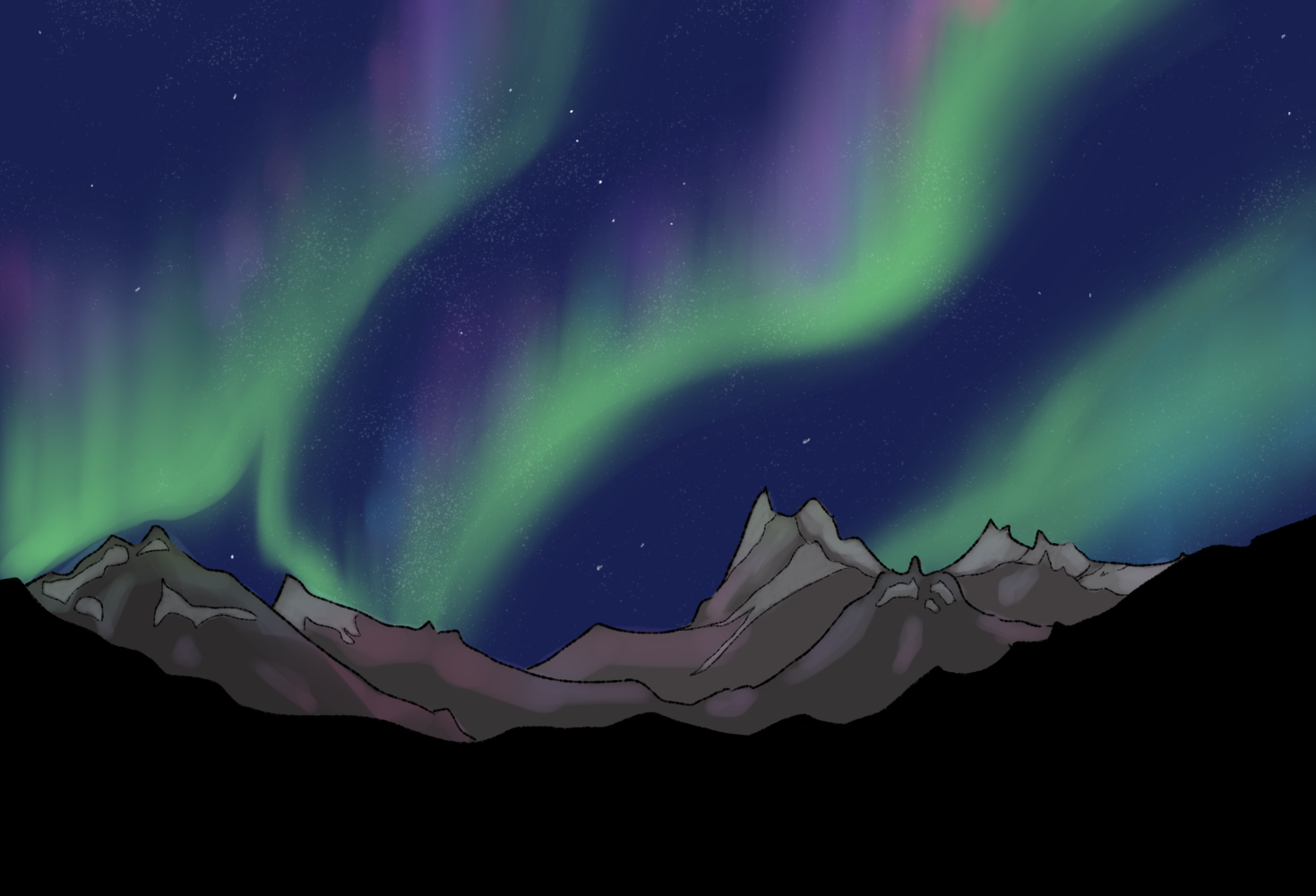

The Art of a Colorful Night

While the polar lights may appear as ribbons of various hues and colors in the night sky, the science behind them is just as fascinating as is their beauty.

Reading Time: 3 minutes

Imagine casting your eyes up into the starry night sky and seeing ribbons of color among the stars. The polar lights appear in the night sky as ribbons of various hues and colors, with the most common being pink and green. However, the lights can also appear red, orange, blue, or violet. While the word “aurora” commonly refers to the Aurora Borealis, colloquially known as the Northern Lights, this phenomenon also exists near the South Pole and is known as Aurora Australis, or the Southern Lights. Both are the same phenomenon, with their only difference being location and name. Galileo coined the term Aurora Borealis in 1619 by combining the word Aurora, after the Roman goddess of dawn, and Boreas, the Greek name for the Northern Wind. The name Aurora Australis has a simpler origin, with Australis meaning Southern in Latin.

Despite only naming the aurora in the 17th century, humans have observed the phenomena for thousands of years. The earliest known recording of the aurora is a 30,000-year-old cave painting in France, with other civilizations, including Ancient Mesopotamia and Ancient China, writing about them in the millennia that followed. However, it was not until the 20th century that the scientific reasoning behind the phenomenon was theorized by Norwegian physicist Kristian Birkeland, despite humans knowing of the existence of the polar lights for thousands of years.

As theorized by Birkeland, the science behind both the phenomenon of the aurora and its colors lies with the sun. At this very moment, the sun is releasing charged particles from its corona, or outer atmosphere, and blowing them in all directions at millions of kilometers per second. These winds are particularly harmful to Earth’s atmosphere and can create geomagnetic storms that disrupt satellites, communication networks, and power grids. To protect us from these “solar winds,” Earth has a magnetic field that deflects these particles towards the poles. The solar wind collides with the upper atmosphere of the Earth, de-exciting the electrons of the gases making up the atmosphere and causing them to release photons of light which appear as different colors. When electrons are excited, they enter a higher energy state for a short period of time. However, when excited electrons fall back to a lower energy state, they emit energy as different wavelengths of light. Each element releases a unique combination of hues, and the atoms the solar winds hit determine the hues that can be seen in the aurora. Each atom has a different number and arrangement of electrons. A green hue, for example, indicates the presence of oxygen, while blue, purple, and pink are caused by nitrogen, the most abundant gas in Earth’s atmosphere.

Unfortunately, it is highly unlikely to see an aurora the further you are from Earth’s poles. Since the poles are where Earth’s magnetic fields are the weakest, the sun’s solar winds are deflected towards them, in turn causing an aurora. If you ever wish to see the Northern Lights, it is best to visit the “auroral zone,” located within a 1,550-mile radius of the North Pole. Some of the best places to see the Northern Lights include Canada, Iceland, and Alaska. Interestingly, however, there have also been sightings of the Northern Lights throughout the world, not just near the poles. For example, the Northern Lights recently appeared in Southern areas of the United States due to geomagnetic storms in those areas, which is a rare occurrence. The Northern Lights appear without a set schedule. To detect them, scientists monitor the sun’s behavior, including solar winds, and although they typically appear within 30 minutes of detection, the Northern Lights can also be detected a few days in advance. To measure the magnitude of geomagnetic storms that result in phenomena such as the Northern Lights, scientists use a Kp-index, which ranges from zero to nine, with nine being the strongest. If you are interested in seeing the Northern Lights, be sure to check that the Kp index is greater than six, as that means that sightings are more likely.

Although we, as humans, mainly think about what happens on Earth, auroras can also be observed on other planets because they are simply caused by the collision of the Sun’s particles with any magnetic field and any atmosphere. To observe an aurora on another planet, scientists use telescopes that detect electromagnetic radiation. While auroras are commonly observed on gas giants due to their strong magnetic fields, they have also been seen on planets like Venus and Mars, both of which have weak magnetic fields.

In New York, you will rarely have the opportunity to see the Northern Lights at home. Thus, if you ever find yourself up north at any point in your life, I implore you to pause and take a moment to look up into the beautiful night sky, for there you will see firsthand a display of one of nature’s most phenomenal artworks that has left humanity awestruck for millennia: the Northern Lights.